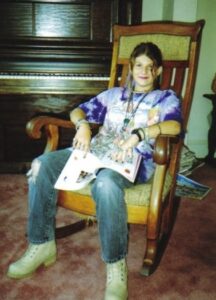

Editor’s Note: The following is a chapter from Eileen Vorbach Collins’ recently published book, “Love in the Archives, a Patchwork of True Stories About Suicide Loss.” When her fifteen-year-old daughter Lydia ended her life, Eileen struggled to survive. She found support in a community of bereaved parents who understood her pain and did not place a timeline on grief. “Love in the Archives” is a moving collection of essays incorporating themes of surviving suicide loss, Judaism, interfaith marriage, and mental illness. We are grateful to Eileen for granting us permission to share her work.

I’ve often wondered if my grief is holding you back. Keeping you from going through wherever it is you need to be. I recently read the greatest gift we can give our beloved dead is to let them go. While a few people have told me I need to move on, no one has offered a clue as to how to do that.

The grief experts have decided I’m sick. Pathological. In need of a diagnosis. After years of debate, they’ve decided on Prolonged Grief Disorder, (PGD) a condition in which there is an “intense yearning/longing for or preoccupation with the deceased person,” and the “duration of bereavement exceeds expected social, cultural or religious norms and the symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder.” Diagnostic criteria include:

• Feeling as though part of oneself has died. ✔

• Marked sense of disbelief about the death. ✔

• Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead. ✔

• Intense emotional pain. (Anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death. ✔

• Intense loneliness. ✔

I’m no expert, just your mother, intensely longing for you well after the six months to a year that’s a marker for inclusion. I’m sometimes still, after 20 years, preoccupied with memories of you. The sad memories haunt me, but I love the happy ones. The birthday parties, our trip to St. Thomas where Helen taught you to free dive. I see you feeding a school of parrot fish. But someone, an expert, or a team of them, has proposed I should avoid even those happy memories. It seems PGD is based on a reward system—the pleasure centers in my brain light up when I think of you. Am I to feel shame because they liken it to addiction?

One small brain imaging study showed the lighting up happened with about half the subjects. I know you would be questioning the validity and reliability. Rolling your eyes at the lack of credibility. The small sample size. The conclusion that deemed the glowing brain parts maladaptive because the subjects continued to crave that feel-good sensation. We often shared such skepticism when you were alive. But maybe they’re right. I’ve been addicted to you since before you were born. First, in love with the idea of you, and then with your amazing, brilliant self.

Supporters of the revision argue the DSM-5 and the International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision (ICD-11) criteria will make it easier for bereaved people to find “treatment.” For years after you died, I tried to find a therapist who took my insurance and who practiced eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, (EMDR) an evidence-based trauma therapy that sounded like it could be helpful. The last time I looked, just about a year ago, I found no one within 50 miles and once again gave up the search. I don’t know whether the inclusion of a new diagnosis, a new disorder, will have much impact on access to services. Still, I’m functioning. Dysfunctioning. Malfunctioning.

After you died, I had to get back to work. Your brother and I needed food and a place to live. Three days is the typical bereavement leave. Seventy-two hours. I still expected you to call for me to pick you up from the library. To slam your door so hard the house shook. To sing to the cat. To play your flute late into the night. Sometimes I heard you, the notes a small, comforting trill as I fell into a troubled sleep. A therapist recommended antidepressants. I declined, certain that would not make my heart stop hurting.

After three weeks, grateful for my employer’s generosity, I went back to work and tried to forget you for eight hours every workday. Forced you into the closet so I could function. And I did.

Six months after your funeral, I continued training, now in earnest and to the point of exhaustion, for that 500-mile bike ride, a fundraiser for AIDS vaccine research. I thought you’d be proud of me if I followed through with it—a plan I’d had while you were still here. I talked to you as I pedaled in Alaska, as I slept in a small blue tent at the foot of a glacier. Wrote your name on the list of people in whose memory we were riding. Most had died of AIDS. The riders who loved them were longing. Remembering. Their grief may have exceeded the duration accepted by social norms, but the light in their neural feel-good centers shone through on many of their faces. Despite the crowd of 1500 riders, I felt intense loneliness. Later, I laughed when your friend told me you’d been skeptical that I could do it. Well, I rode the sag wagon a few times. But I finished my one-and-only century on the first day. I was functioning to the best of my ability, preoccupied with thoughts of you the entire time.

The experts led me to believe one year would be a turning point. That when 365 days and nights had passed, I would be able to pack you away like yellowed letters from a long-forgotten lover—that time alone would have mended my shattered heart. I’m no science denier, but I fear the experts may have missed the mark here.

No one told me the second year is often worse. That the shock would wear off, replaced by the grim reality that I would never see you again. One year after you ended your life, the force of your absence pounded me with gut punches that knocked me to the ground. Still, I got up in the morning. Went to work. Shopped for groceries. Functioned. Dysfunctioned. Malfunctioned.

The literature is clear that parents grieving the loss of a child and those whose loved ones died suddenly or violently are more at risk for being in the 7% of people who will fall into the criteria for PGD. How odd then, that in the more than twenty years since I tried to breathe you back to life, I’ve never met a bereaved parent who doesn’t say with absolute certainty that they will never stop grieving.

We’re not being morose. Our bodies are no longer wracked each day with sobbing. Our eyes may not be puffy and red. We’ve had moments of joy and hope to have many more. When we gather, we can light up a dark room by the collective glow of our nucleus accumbens, that feel-good brain part most commonly associated with reward. We share photos and talk about our dead children like normal people talk about their living ones.

For all the experts who think we should be over it, I’m going to light up my brain with images of you as often as I can. You’re my addiction and I’ll cry if I want to.

I’m no expert, just another grieving parent with a new diagnosis. Look, I’m writing a letter to you, and you’ve been dead for more than 20 years. I must have Prolonged Grief Disorder. But I wonder, are we who refuse to sever ties with our beloved dead, the ones in need of treatment? Might the effort to arrive at a diagnosis be better focused elsewhere?

We need to ditch the toxic positivity. I don’t want to hear you’re in a better place or that God doesn’t give us more than we can handle. Of course, I count among my blessings that I have another child. Most of all, I don’t want to hear that time heals all. I’m the expert there. I and thousands of bereaved parents know it doesn’t. Over time, the intense pain of the loss will fade. But my yearning and longing for you may never cease. Instead of labeling us with a disorder, I wish they’d ask your names. Allow us to share our memories and watch as our faces light up with pleasure at the memory of you. Even stick around if we’re feeling sad.

The only thoughts and prayers I have for other bereaved people are these: In the difficult years ahead, may the pleasure centers of your brains light up often. I hope you never feel rushed to get over it. May you not hesitate to speak your child’s name, and may you often hear it spoken, if that brings you comfort. I refuse to pathologize that. Our memories are all that’s left. Maybe that’s an addiction, but I call it love.