I read somewhere, during the first year following my son’s suicide, that it takes an average of X years to fully integrate a suicide loss. I intentionally plugged in the letter X because we’re all on different timelines; suicide is not one size fits all.

For a time, I thought I knew what integration meant. I thought it meant I would get back to who I was in terms of being fully functional. I thought it meant that I would once again operate at the level before my son’s death. I thought it meant that I could enjoy life again without survivor’s guilt and with a good night’s sleep. I thought it meant I would no longer need to rely on individual counseling or group therapy.

I was wrong. Integration of a loved one’s suicide does not guarantee well-being. Integration guarantees nothing, nor is it easily recognizable. Integration of a suicide loss for me is unique to me, just as integration of your suicide loss is unique to you. Integration isn’t something you look for but something that will find its way to you.

For me, integration turned out to be more about feeling and less about thinking. For the first two years or so, I spoke to my son every night, but no matter what I said, no matter how I started my monologue, it always led back to the same place: “I’m sorry. I wish things were different. I’m sorry. I wish it had been me instead of you. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

So why did I talk to my son every night? Because the moment the umbilical cord was cut, my son was his own person, physically detached and completely autonomous. After he died, he was still detached, no longer existing, but autonomous just the same. And since I spoke to him in life, it made sense to continue to do so, even in death. Especially in death.

Gradually, as more time passed, I continued to speak to my son at night, but I’d forget from time to time, and this made me feel guilty. I felt guilty that I wasn’t saying the same thing over and over again every night to someone who may never hear me and who can never respond. I felt guilty that I may be forgetting my son as the cares of the day came to preoccupy my mind. I felt guilty for beginning to feel less guilt.

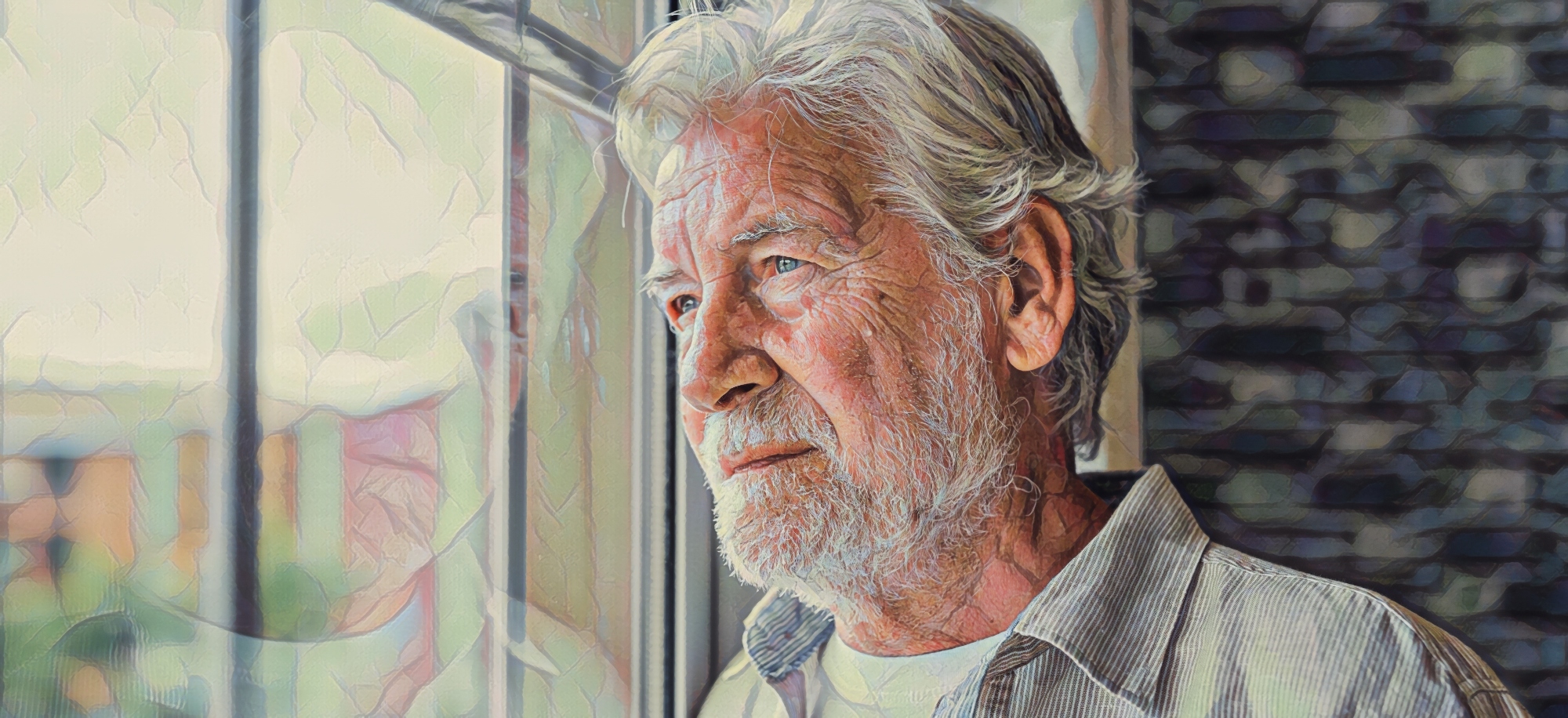

I started talking to my son tonight, more than four years out.

I hadn’t talked to him in a while, and I started my monologue the same way I always do: “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m sorry” … and then it hit me. I don’t feel the need to check in with my son every night because he is no longer detached. He is a part of me, but not in the same, natural, and nurtured way he was in life; this is difficult to explain, but I’ll do my best.

We often hear that death changes us, but how many of us stop to think that it’s the one we lost who is affecting that change? I mean actively as opposed to passively. Just because our loved ones are no longer here with us does not mean that they no longer have an impact on our lives, that they can no longer play an active role in shaping who we are, that they are not, in effect, acting through us.

I’ve become a more compassionate person as a result of losing my son, but I neither give myself nor death, credit for that, instead, I give it to my son. I am more self-aware than I’ve ever been before and again, the credit goes to my son. I strive to make a difference in the lives of other survivors, thanks yet again to my son.

For me, integration means acknowledging that my son is acting through me by helping me to make a difference in this world, however small, however fleeting. Would I rather he be here, autonomous and breathing? Absolutely, but that will never happen. So, what is the next best thing for me? Allowing him to impact my life, actively shape who I am, and, in effect, allowing him to act through me. This is how integration found me.